overview

overview

Andrzej Kenig wants to start his life over after the war. He goes to Siwowo, where he is to it guard from looters. He meets doctor Milecki, who starts to behave strangely once he gets to know him. When Kenig realizes that Milecki is the leader of a gang of looters and the chances of him being caught by the police are faint, he decides to work alone…

storyline

storyline

Andrzej Kenig fought in the Warsaw Uprising and was later in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Just after the war in Warsaw he did not find any traces of his close ones, so he takes the train to the Regained Territories. He wants to begin a new, quiet life, make a living, find a wife. On one of the stops he joins a group of five led by doctor Milecki. The group, as per the orders of a government assignee, is to go to Graustadt city (renamed the Polish Siwowo) to prepare it for the arrival of repatriates and protect it from looters.

On the market in Siwowo the men meet four women returning from the camp – the first relationships begin. Kenig takes a liking to Anna, an introvert, quiet woman who lost her husband during the war. They separate from the rest and visit a few abandoned flats in order to find Anna a dress. On one of the streets they run into a drunk German man who remained in the city. He turns out to be a waiter from a nearby hotel. He organizes an evening full of alcohol for everyone.

Kenig is more and more surprised at the way doctor Milecki talks and behaves, as well as his companions: they ask the waiter if there are any trucks in the city, they look for valuable objects in flats and basements. Kenig realises that they are a gang of thieves who want to run away abroad with what they have stolen. He is also soon certain that Milecki will have no boundaries in achieving his goal: he kills a policeman who has come to the city as a special legate of the government assignee, and also murders Smółka – a simple boy from his group who one day comes to his senses and tries to stop the doctor from robbing medical equipment from the nearby health resort.

Milecki tries to buy Kenig’s silence. He proposes to give him ten percent of what will have been stolen. He does not know that Kenig has already found a working phone at the post office and has informed the authorities about what is going on in Siwowo. However there are small chances that the police will come before Milecki’s group runs away. Kenig is on his own. In the morning when the men start off the trucks with the belongings, he shoots the tires and stops them from moving. Firing begins. Due to a deceit, Kening kills Milecki and two others. Anna leaves the city. After what has happened she cannot be with Kenig. Kenig is left completely alone.

comment

comment

press review

press review

“The Law and The Fist”, through its main character, refers to motives of the ‘Polish Film School’ which are not yet closed and definitely not exhausted. Behind the drooping back of Andrzej stand the war and occupation. He is a man who has experienced his share of danger, pain and poverty. He does not appreciate glamorous gestures, does not strike expressive poses – there isn’t a thing he would do to show off before others. He seeks peace, a basic well-being and safety. He does not even know that he is a ‘nonconformist’ until a situation he would never want to be in makes him behave that way. However the situation did happen and it made way for the deeper layers of the psyche – shaped by his experience just as much as the more shallow layers – those, which make him counteract evil (…). The creators of “The Law and The Fist” have achieved something very nontrivial: they managed to preserve realism even in the ethical sphere and to avoid an easy depreciation of non-heroic attitudes.

Wiktor Woroszylski, Polish western, „Film”, 1964, nr 39

The most important meaning of this film in our cinema is that although it is a western born out of Polish situations, it has taken away the apparent unique exoticism from the American western, that through speaking about our affairs it has made western events and conflicts more probable and the western schemes have become less abstract and more realistic. In it the people and characters can live a normal life, not a delusional one (…).

The film is perfectly built when it comes to drama, it has excellent points, a good tempo, and Kenig’s scuffle with the looters – abounding in emotional and effective moments – was staged with knowledge and impetus. “The Law and The Fist” is probably one of the best realised Polish films in the last few years, a film which is no worse than any good American western when it comes to discipline and mastery.

Józef Hen paid the deepest attention to the character of Kenig, a participant of resistance movement and an educated teacher who has had difficult war experience, in his script. His loyalty to basic moral values and social norms is not only idealism or assets with no covering. Gustaw Holoubek has played this role fabulously – with tact and moderation and a big evocative.

Kazimierz Kochański, The Law and The Fist, „Tygodnik Kulturalny”, 1964, nr 39

When making their pastiche of a western the authors used a perfidious and original directing stunt: they left the mystery to the audience and did not fully show their cards and intentions. So they did not place the story in the Wild West, but on the Polish Regained Territories and they did not make their characters wear comedy clothes, like most directors who make parodies of westerns do (we know films like that, especially French with Fernandel and other comics), but told them to wear typical clothing of Polish Regained Territories settlers from 1945, Polish policemen and Polish soldiers. So the viewer falls into the trap at first, treats the film seriously as a memory of difficult and no less dramatic stories than those from the Wild West and only gradually realises he has been invited to a humorous game.

Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz, Blind man’s bluff game, „Świat”, 1964, nr 40

Recently Jerzy Hoffman and Edward Skórzewski debuted with a feature comedy film “Gangsters and Philanthropists”, and now they have presented their second film “The Law and The Fist”. In both of these films we see an ambitious, entertaining creativity with a conscious – lacking an inferiority complex towards so called serious genres – turn towards entertainment films and achieving perfection in its realisation, while at the same time saying something important and original about reality. (…) Fist fights, gun shots, chases, scenes full of tension. Hoffman and Skórzewski are amazing about juggling surprises, they take away all chances from the main character to surprise the viewer with a great trick, ploy and courage, to make victory even harder to achieve. All of this shows an excellent feel of the situation and the drama of a sensational-adventure film.

Of course this does not mean that the realities of “The Law and The Fist” are identical to the reality of the American West. The directors deliberately choose special situations, deliberately stop by elements which make way for a comparison to westerns in order to show a sum of truths about the first difficult post war days on the Polish west.

Janusz Gazda, In the circle of ambitious entertainment, „Głos Pracy”, 1964, nr 220

The character closer to the viewer is always the weaker one in a western. His chances are smaller. Either he gets trapped or must fight against more than one enemy. Here a double reinforcement is in place. In this case the film refers to a basic feel of justice in the viewer. (…) In the fight for justice the character in the western risks his own life. The risks he takes make his case stronger. It makes him a real hero. Therefore the viewer identifies with him more eagerly. (…) Due to the mechanisms detailed above a western can be a very effective means of popularizing moral norms. Hoffman and Skórzewski have used the convention of a western in that very cause. That is above all what they have taken from the western. And they have taken the best part.

Jerzy Niecikowski,The Law and The Fist – for the second time, „Kultura”, 1964, nr 40

did you know?

did you know?

Józef Hen’s script first interested Witold Lesiewicz, who previously made „April” with Hen’s script. The director made the first pictures and prepared a storyboard, but then – as Hen put it – it turned out that the subject did not interest him that much. When Hoffman and Skórzewski found out they immediately said that they would like to make the film.

Stanisław Zawiśliński, Hoffman - hooligan life, Warszawa 1999The popularity of the film made Hen change the title from “Toast” to “The Law and The Fist” when ‘Literary World’ renewed the novel in 1996.

Working titles of the film: „Toast”, „Six pistols”.

Czesław Petelski also wanted to make a film based on Hen’s „Toast”.

Filming locations: Toruń (Nowy Rynek, Pochmurna street, Mostowa street), Chełmża, Ciechocinek.

„The Law and The Fist” along with „Echo” by Stanisław Różewicz represented Polish cinema in 1964 at the festival in Karlove Vary.

The debut of the film was in the cinema „Grunwald” in Toruń.

In the novel and the first version of the script there was a Jew Cukierman, who was the first to organize life in the city and who was killed by the looters. Hen was then accused of making an impression that Polish people killed Jews. Hoffman, in order to avoid similar problems, asked Hen to remove Cukierman from the script.

Jerzy Lipman – the author of the photographs for „The Law and The Fist” – wanted he film to have a dark, cloudy tonality. Only the last scene is in the sun.

The making of the film began on 19 March 1963.

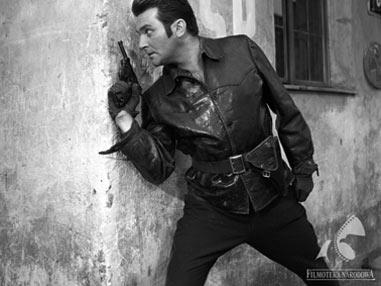

posters and stills

posters and stills

In the photo: Gustaw Holoubek

In the photo: Zofia Mrozowska

In the photo: Ryszard Pietruski

In the photo: Gustaw Holoubek

In the photo: Wiesław Gołas

In the photo: Jerzy Przybylski

In the photo: Aktorzy i ekipa filmowa

The drama is almost like in a western. We want to make a realistic psychological film which takes place in typical Polish conditions, and at the same time an adventure film – said Jerzy Hoffman and Edward Skórzewski during the making of the film “The Law and The Fist”.

„Film”, 1963, nr 41

The directors are walking through a minefield. The book they based their film on, “Toast” by Józef Hen, was called a Polish western from the beginning. The directors emphasize that they have done everything in order to underline the western convention in the film. This could be taken as a provocation, because the few previous attempts of making a western in the Polish reality were fiascos. After a complete disaster of one of them, “Rancho Texas” by Wadim Berestowski, Zygmunt Kałużyński even claimed that a western is the child of American culture and therefore cannot be successful anywhere apart from America.

Despite this Hoffman and Skórzewski were successful. Most of all because they showed specifically Polish motives in the film. These were in fact visible in all of Józef Hen’s work: 1945 as a moment when war gives in to peace, the Regained Territories as the place of action and the main character, who despite the dramatic experience of war did not lose his humanity and moral values. All of this made “The Law and The Fist” not an attempt to copy the American model, but a film which proved that western conflicts were not reserved for the Wild West. However Skórzewski and Hoffman went even further - they showed that the conflict from “The Law and The Fist” is much more complicated.

“In classical westerns – they explained – the main character, in the moment he puts on the sheriff star, is in a way already absolved and it is obvious that his every gunshot will be just. The convention of a classical western also assumes that the number of accurate shots and corpses does not count. Everything is arbitrary, so there is no drama in death. However (…) it would be incompatible with the Polish psyche if someone – apart from the criminals of course – decides to kill his enemies without hesitation. So in this case the metaphoric sheriff star does not excuse our main character in the eyes of the Polish audience.”

„Film”, 1964, nr 40

COLUMNBREAKPOINT

The main character that the directors spoke about was played by Gustaw Holoubek, which was extremely surprising to both the audience and Józef Hen himself, who could not imagine Holoubek as someone “in Gary Cooper’s type”. In “The Law and The Fist” Holoubek distanced himself in an interesting way from his intellectual employ. He was still an intellectual, but a bit more active, more determined, who – in a moment of numerous doubts – could choose a concrete answer: be active, counteract. The ballad “Before the day rises” by Krzysztof Komeda, with Agnieszka Osiecka’s text, which became one of the most popular film songs, is a characteristic tie and gives the whole film a tone of hope. Kenig is psychologically broken after the scuffle with the looters, but he has not lost completely. The words ‘a day is rising’ sound especially strong.

Commentary: Jerzy Hoffman