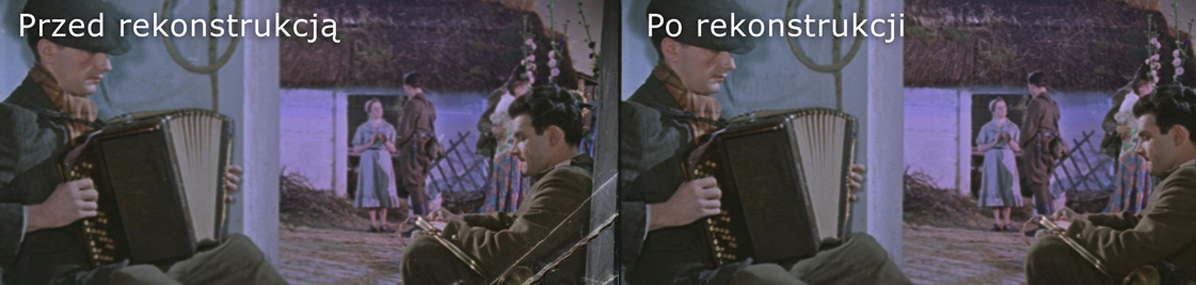

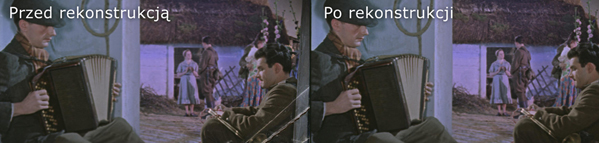

One of the elements of pre-war film reconstruction is its filmographic study. It encompasses establishing as much information about the film as possible, about its background, the crew and the cast. When preserved footage is incomplete and in very bad condition, it is essential to thoroughly analyse the remaining parts and to ‘compose’ them accordingly.

In Poland pre-war film reconstruction is a new field which hasn’t develop its own jargon yet. As for the methodology, film studies do resemble textual studies and scholarly editing very much. This association’s given me an idea to use academic vocabulary from those fields when working on an archival movie at some stages.

In most cases filmographic work starts with looking through the tapes manually and comparing them with each other. At this stage so called ‘editing list’ is being created – it is a list of all the shots in the film – and information regarding the presence of the given shot in every print and whether it is complete or not is being added to it. In scholarly editing it’s called collation (from Latin collatio). The thorough comparison – shot by shot, frame by frame – of all the preserved footage is not unlikely to lead to very interesting discoveries shedding new light on an apparently well-known film. Above all, particular prints have proven to vary from each other, mostly due to the tapes’ degradation: certain copies were lacking small or big parts which could be usually found in the other footage.

il. 1. Przekopiowane rysy i sklejka na obrazie w filmie „Sportowiec mimo woli”.

In order to know the film well, it is not sufficient to watch it on a big screen. Many times did I learn that it is essential to find the original tape[1] and look at it carefully. The footage on the tape recorded as a set of frames is not all. Studying the history of a film, things that are not visible during the viewing, therefore apparently insignificant, can often be found important: the name of the producer of the film tape, the type and the quality of the tape, the condition of it and the kind of defect, the type of splice, whether the splice and the damage are actually on the tape or were copied from another medium etc. Additionally on the edges of some tapes, there are dates of production encoded. It makes it possible to state whether the tape is an original or a print that was made later.

The example of The Accidental Sportsman proved how important can apparently insignificant details be. I was intrigued by the title sequence to that movie for a long time. It’s very different from the other title sequences to Polish films from that time, additionally it contains this other title: Romans w Zakopanem (Romance in Zakopane). It was the first sign that the movie could be hiding a secret. During conservation, I noticed another interesting fact: on the tape there were visible numerous splices copied from the previous footage. It became clear that it is not an original but a print made from another tape. Interestingly enough, the splices were visible only in the picture, soundtrack however was continual. What was intriguing as well was that the film was very grainy but the soundtrack was almost intact. In normal situation it would be impossible, the whole tape would be damaged. After scanning and playing the movie, I learned that despite the soundtrack was ‘clear’, loud cracking and static could be heard which is typical for a very scratched film tape in poor condition. That was another mystery.

In our archives we have another print of the film preserved which hasn’t been screened after the war. We discovered that it includes so far unknown beginning of the movie with the original title sequence from before the war which is very similar to the title sequence from the film Włóczęgi (The Vagabonds) produced at the same time. It was confirmed that there must have been two versions of the same movie released.

Some scenes in the film seemed unusual as well. Title cards ZAKOPANE and HOTEL BRISTOL appearing on the screen were incompatible with the rest of the film. Some scenes showing the winter sports were strangely edited, additionally some shots copied from Biały ślad (White Track) from 1932 were used. The ending of the film raised some doubts and aroused suspicions, too.

il. 2. Oznaczenia na krawędzi taśmy w amerykańskiej wersji „Sportowca mimo woli”.

That was a clue. The font used in the trailer was the same in the credit titles and in the two title cards mentioned above, therefore the trailer must concern this version. Based on the marking found on the edge of the tape the film was recorded on, I came to a conclusion that the tape alone (as a material) must have been produced in 1927, 1947 or 1967. The year 1927 can be ruled out because it’s not a silent movie; 1967 as well because production of nitro tapes ceased earlier. The only one left was the year 1947. Finally everything fell into place. It was discovered that the footage known until then was a version produced in 1947 that was comprised of preserved parts of the movie and was destined for the United States of America market.

While working on the film entitled 1863 from 1922, I came upon a similar surprise. There were also two versions of the film preserved which considerably varied. Above all, the colours used in them were completely different. The graphic design of the intertitles was different in each copy; some cards showed different titles and not always did they appear in the same spot which sometimes changed the meaning of the dialogue. Some shots and sequences were presented in different order. In one version there was an abundance of morphing, multiple exposure, adding titles to the movie and other effects which were not in use at that time. After a thorough research, I realized that 10 years after it had been released, the film was reedited, altered and re-released.

il. 3a. Zapis dźwięku na tej samej klatce z wersji pierwotnej

il. 3b. Zapis dźwięku na tej samej klatce z wersji poprawionej.

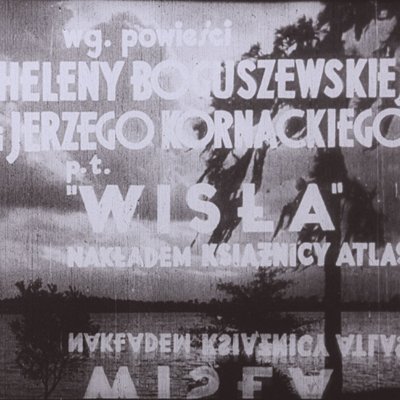

Another example is the film Vistula People. There are two prints of the movie preserved. Both title sequences are very similar but they’re not identical. The content of the titles, the font and layout are the same but the titles in the first copy are ordinary and single and in the second one they seem to reflect on the surface of the water. The background in both title sequences is the same, however it must’ve been shot differently. Probably the version with the reflection was the first one, than the film-makers came to a conclusion that the titles weren’t clear enough that way and they changed it and made it simpler.

il.4a. Czołówka w wersji pierwotnej.

il.4b. Czołówka w wersji poprawionej.

il. 5a. Usunięta scena z wersji pierwotnej

il.5b. Scena dokręcona po interwencji cenzury

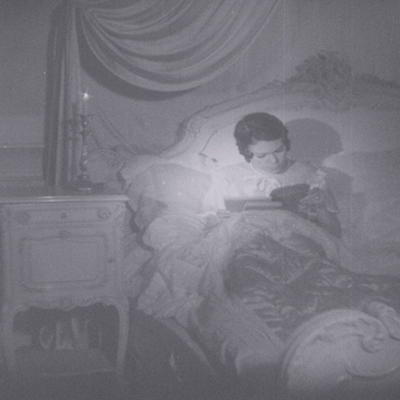

General Pankratov's Daughter proved to be particularly intriguing. Two different version of the film have been preserved and the reason for the second one to be created was the censorship. The censors were especially appalled by the scene where, as the result of conspiracy, the general is being shot by the Polish revolutionary. The scene was removed and shot anew: when hunting, general Pankratow and his companions come across a group of revolutionaries having a meeting in a forester's lodge. The shooting starts and the general is injured. The scene must have been shot in haste – it’s artistically and technically inferior to the original. The other difference is related to the scene where Aniuta, who’s constantly more and more fascinated with her Polish origins, sits at the piano and sings parts of Warszawianka to Aleksy for a while, just to stop and say: ‘Come on, it’s a joke…’. Calling a patriotic song ‘a joke’ was unacceptable at that time. In the other version the scene has been changed: at night Aniuta is secretly reading Polish history textbooks and Mickiewicz’s poems. Interestingly enough, until recently the only version we knew was the one from before the censorship interference.

When we’re dealing with two versions of the movie that vary, we are facing a dilemma: which version should be reconstructed? Of course the best solution is to restore the original… but which one is the original? It needs to be established, what is the reason for the discrepancies in the two versions. It’s easier when the film was banned by the censorship and changed as a result of that, but what if it was ‘enhanced’ and re-released (like 1863)? What proves to be helpful is experience and textual criticism. When we have already chosen the base for reconstruction, so the footage we consider to be the right one, it is essential to analyse all the differences frame by frame. If there is a scene in the other prints which the base version lacks, we need to establish whether it’s not there because of some kind of degradation (then it needs to be completed) or was it deliberate editing procedure (then we need to ignore it). Sometimes the decision is easy to make, almost obvious, but it may also be very hard to make, even impossible. Every time a historic item is being reconstructed, there’s a risk it may not correspond with the original or the author’s idea. The same applies to films.

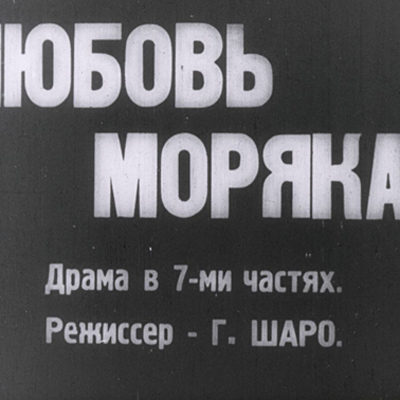

il. 6a. Zagraniczne plansze tytułowe do polskich filmów: „Zew morza” w wersji rosyjskiej.

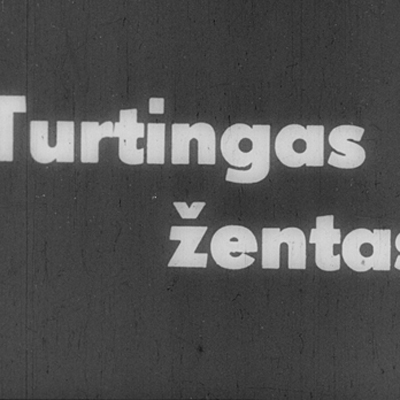

il.6b. „Jego ekscelencja subiekt” w wersji litewskiej.

What proves the film was popular (even if indirectly) is the number of preserved prints. For example there are five original release prints from before the war for the movie entitled Ty, co w Ostrej świecisz Bramie (Hail Mary, Full of Grace)! Of course not all of them are complete, some include just some short sequences. Preserved footage from Paweł i Gaweł (Paweł and Gaweł) come from as many as nine different prints. Presumably there had to be more of them. If so many prints were produced, we have every right to assume that the film was very popular.

Interestingly enough, most Polish films distributed in Polish community centres in United States of America had their titles changed. For example The Two Joans was screened as Love Conquers All; Women on the Edge as The Spider, The Accidental Sportsman as Romance in Zakopane, Księżna łowicka [literally translates to Duchess of Łowicz] as November Night etc.

Within the confines of filmographic work, we also create a new database of Polish pre-war cinema. We’ve started with 43 films included in the project and people connected with it: the cast, the authors and the film crew. If possible we are trying to create new biographic entries and descriptions of the movies relying only on sources from before the war. Through the decades, many myths have been invented and misrepresentations have mounted around some people and films. We often come across misspelled surnames or realize that the actors were identified incorrectly. One could think that the most reliable source of information about the cast would be the opening credits but they can be very misleading, too: misspelled surnames and changed names. For example in the opening credits for Romeo i Julcia (Romeo and Julie; which undoubtedly is the original) the name of Maria Betcherowa can be found. Surely someone meant Stefania Betcherowa, a great character actress. Looking for information about some people is indeed a detective work during which we can sometimes come across contradictory leads which are responsible for the mistakes and misrepresentations that have been repeated for years in many academic works. We’re trying to reach the source materials from before the war and compare, interpret and compile them once again. Where to look for such information? It’s impossible to give a hint. Very interesting information can be found when we least expect it, for example we’ve got the articles on making of Pan Tadeusz from women’s magazines. What proved to be another great source was... the radio press. As it often happens during such research projects, the most sensational discoveries were made by us by accident.

Pre-war film is a work that has a long history which has started a few decades ago, that was through a lot and was subject to change. Every movie has its own history, its own mysteries and is full of different surprises. It requires individual approach which makes filmographic work a truly fascinating investigation. I’m sure there’s more than one discovery ahead.

Translated by Karolina Fryszkowska

[1] As far as the film is concerned, the term ‘original’ is a problematic one because film is a copy by definition. I mean the access to the oldest release prints from the time when the movie was being released.