Just as film stock has a limited resolution, so too does the human brain.

Julian Antonisz[1]

The preservation of new media art has developed in isolation from the ‘traditional’ conservation and restoration practices of cultural heritage, mostly due to the relatively short history of these media, and the fact that film conservation has been the subject of scientific research for no more than a few decades. This has also been caused by the impact of a film industry — disproportionately high compared to other fields of art — as well as the popular belief that moving image recorded on film is merely a ‘reproduction’, that is not unique, and as such beyond the interest of art conservators/restorers. However, this situation has changed with the transformation of the medium itself, in the transition from analogue to digital. A digital copy can be reproduced ad infinitum, whereas film stock is prone to damage and deserves to be given the status of cultural heritage which it was hitherto denied.

Julian Antonisz’s non-camera films are a case in point, epitomising all of the above problems — work on their preservation was the result of a compromise between the conservative approach to an artwork, typically considered as a unique result of the labour of an artist, and its conversion into the film medium. Antonisz’s works are absolutely exceptional in the entire collection of the Filmoteka Narodowa (National Film Archive). The project of a digital restoration of such material was equally unprecedented. It soon became evident that the digitisation of these films required an in-depth analysis of the artist’s output: not only with regard to the reels of 35 mm film stored in the Filmoteka (negatives and material distributed to cinemas), but also the general context of the artist’s practice.

Polska

The work of Antonisz is an example of auteur cinema, recognisable from the first frame, as ‘an attempt to turn back time to the age of handicraft’.[2] With an enthusiasm worthy of an inventor, the artist developed ever new ways of adapting known printmaking techniques for the needs of film: from surface, through intaglio, relief, to screen print. His ‘ideabooks’ include numerous accounts of technological experiments involving readily available materials — popular objects that were dissected by Antonisz.

He studied the effects, assessed the potential utility of the representation of the texture of a leaf, or the trace left by a thread dipped in paint, and analysed these things: ‘Burning out the tape gives an effect of three-dimensionality. Collage, i.e. pasting different textures and materials, e.g. documents of nature, such as insects, flowers, etc. expands the field of an artist’s work, depending on the degree of translucency of the material.’[3]

Antonisz’s non-camera films can be divided into two types with respect to technique[4]: imprinted and scratched (involving painting/drawing). Interestingly enough, for both methods the artist used his own tools and unconventional solutions: ‘If you want to paint with ink on celluloid, wipe it with a cut potato.’[5] The templates for 35 mm impressed films, with which the artist ‘printed’ the individual frames, were made of different metals: aluminium, copper, zinc, as well as wooden blocks and linoleum. 'Sun. A Film without a Camera' (1978) was made completely with the use of a method that resembles woodcut printing, with the difference that the blocks were impressed directly onto the 35 mm film stock rather than paper.[6] As it turned out, the best base for non-camera works was a film stock cleaned of emulsion: i.e. a slow-burning celluloid produced on the basis of cellulose triacetate. Most of Antonisz’s films, however, were not ‘printed’. The artist worked on them using specially constructed machines, with which he scratched out, scraped and carved, thus developing his second technique of painting/drawing.

The system of work in the painting/drawing technique can be divided into three stages. The first stage consists in scratching out the image on the film stock, cleaned of emulsion, with the use of a special pantograph of the artist’s construction: ‘On large-format paper I draw, with a pencil connected to the pantograph, an image of my choice, which the apparatus scratches out on the film with a special stylus, of course, adequately scaled down.’[7] In this way, a ‘latent’ image appeared on the celluloid film, which was then ‘processed’ in the next stage by rubbing a transparent shoe polish and soot into the scratched-out contour. The latter was obtained in a ‘soot generator’,[8] built especially for that purpose. The last stage belonged to the artist’s wife who, like the female workers at the Pathé factory[9] in the early 20th century, coloured each frame with spirit-based felt-tip pens and translucent watercolours. Painted on fragments of film stock, the sequences were then edited into reels which — as one can read on the cans — constituted a ‘priceless original’. The image from film prepared thus was then projected onto the wall from a projector, also built by Antonisz, and filmed with a standard camera; the resulting negative was processed using laboratory methods. This marked the end of the non-camera process, but not the end of the work on the film. The artist not only scratched out and painted the images, but also combined them with live-action scenes — thus referring to, for example, Georges Méliès’ trick films. Once processed, the negative was ‘cut’, that is edited according to the filmmaker’s suggestions. It was only at this stage that the previously shot live-action scenes were included in the film.

A parallel ‘production’ stage focused on the preparation of a non-recording soundtrack. In accordance with 'The Structure of the Model and Organisation of Production of Non-Camera and Non-Recording Films —Graphic, Artistic'[10] — the sound could be hand-drawn on the film stock or scratched out with the help of a machine, such as the ‘razor-blade-ophone’. The soundtrack could be also applied directly onto the film with the use of ‘sound stamps’; in this way, the artist excluded electrical devices of any kind from the process of working on the sound.[11] After the editing, the hand-made soundtrack was exposed onto the film stock. This is how a reverse colour-graphic recording (the so-called sound negative) was prepared, which was then edited and exposed together with the negative image in the next production phase. Other intermediate materials (the dupe positive and the dupe negative) were also created in a process which culminated in the production of the master print of the film. Material thus prepared could be used to produce numerous cinema copies, but there still remained the issue of the imperfect photochemical processing and the specific colour of the emulsion of the ORWO film stock.

Antonisz manifested his dissatisfaction with the result of the complex laboratory processing and post-production on many occasions. He disagreed with the opinion that animated film had a ‘reproducible’ character, and strove to elevate non-camera to the rank of painting; in one interview he said: ‘The filmmaker, who is most often an artist, draws the whole film on paper or celluloid, either by himself or with the help of a whole group of people, frequently creating an original work. And then he makes its copy, scaled down and inferior with respect to artistic qualities. The original artistic compositions, that which is most important in art, lands in the bin.’[12] He dreamed of skipping the whole laboratory stage, which was not directly dependent on the artist but on anonymous technicians.

The above description of the production technique of Antonisz’s noncamera films was based on, among other things, the artist’s rich archive, conversations with his daughters, Sabina and Malwina Antoniszczak, as well as analyses of the film material made available by them. Such information makes it possible for the conservator/restorer to undertake key decisions regarding the choice of the output material, as well as the way it is to be stored, copied, and made available. This information was used in the course of the digitisation process of Antonisz’s non-camera films, a part of the restoration project launched by the Filmoteka Narodowa in the Autumn of 2011. The endeavour seeks to protect and digitally restore the films from the collection of the Kraków Animated Film Studio. As the result of the project, we have digitised 20 out of 36 of the films created without a camera.

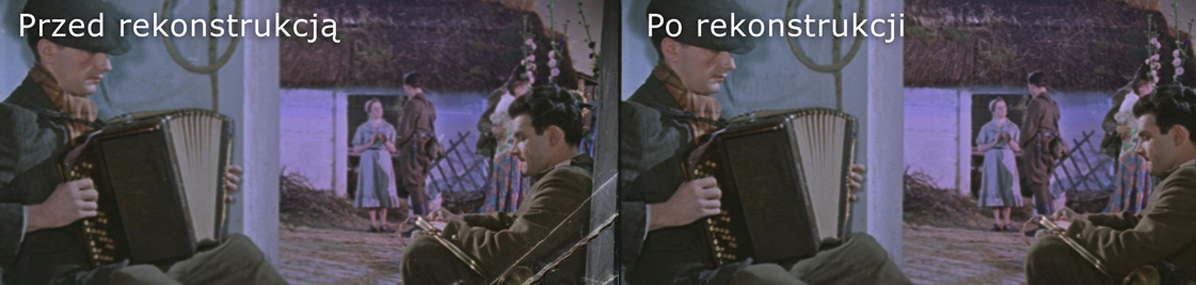

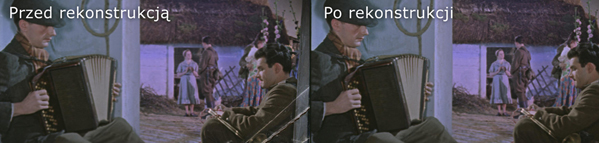

We began the conservation and restoration of Antonisz’s films using a conventional procedure. Working with conservators from the Film Archive and experts from the Hungarian studio Magyar Filmlabor, we established that camera negatives and magnetic sound prints would serve as the best source of image and sound to be used for digitisation. The condition of the materials varied, and the ORWO stock, widely used by the Kraków studio, had changed its colour properties, making colour correction a necessity. Without prior knowledge of how the hand-made source material looked, and having at our disposal only the duplicated material (prepared using the method of optical printing), our initial conclusion was as follows: in order to approach the mysterious notion of the ‘original’ in the course of digital restoration, it is necessary to gain detailed knowledge of the source material of these films.

Sabina i Malwina Antoniszczak

Praca nad filmami Antonisza

Sabina and Malwina Antoniszczak, who have an extensive knowledge of the films as well as their source material, have offered their assistance. Expanding the restoration process to include something that is an ‘original’, in a museum sense, and following Antonisz’s unconventional thinking, meant a minor revolution in the concepts and strategies of work hitherto used by film archivists. 'The idea is that our commercial film has been dominated by technicians and engineers. We are overwhelmed by copies, negatives, processing. Whereas in this case, it’s as if film returns to handicraft, to its very origins. And this is the moment it becomes a unique work of art. [...] Film made using a camera is a slavish copy of the reality in front of the lens, whereas a film that makes do without a camera is a priceless original'.[13]

The above statement by Antonisz offers the following conclusion for the conservator/restorer: the process of the restoration of the films, if it aims to convey the expression and aesthetics of the artist’s non-camera works, must be based on a documented interpretation of this material coming from the artist. According to popular opinion in archive circles, the ‘original’ film print is the one which was screened for the public for the first time, another popular concept has it that the camera negative is the original source material for the image. It is often believed that an archive which has access to both the negative and the master print (approved by the filmmakers at a pre-release screening), has everything that is necessary for a successful restoration of a film work. In the case of Antonisz’s unique non-camera technique, the material collected by the archive might prove insufficient. One has to again seek the answer to the question: where (and what) is the original? The problem is nothing new in the era of mass reproduction: from the beginnings of photography, through film, to the present times of digital media. From the beginning a film negative was used to produce many copies, this is why the question of an ‘original print’ is irrelevant, while the criterion of an original ceased to be of paramount importance for the reception of the film. Antonisz’s film output, however, challenges everything that happened with the concept of the original from the moment photography was invented, and reinstates the older cult of the authentic and of original matter. It challenges the value of copies and replicas produced out of necessity, and that have a weaker effect than their non-camera originals. And as much as the photochemical technology is based on reproduction, the reproduction itself has its own limitations in the ‘traditionally’ produced films, which need to take into consideration: the criterion of the generation of the film material, the fate of individual copies, and the work of artists done directly on the film material. The films of Antonisz are first generation — a pre-negative, ‘handicraft’ which bears the individual mark of the artist’s work with the film stock. Their texture, the light introduced by puncture holes, the original vivid colours of felt-tip pens and ink — all that which cannot be transferred completely onto the low-quality ORWO stock, was frequently emphasised by Antonisz: ‘Hand drawn and painted images on 35 mm film offer sharpness, contrast and intense colour otherwise unattainable by photographic methods. The vibrating colour highlights the proximity of the artist’s hand and thought.’[14]

For this reason, on the occasion of high-profile screenings Antonisz showed his works from the original, hand-painted film, using a projector with numerous ‘improvements’. At the same time, his films were widely accessible owing to the traditional methods of production that included the negative and the positive print. Copying onto the negative was essential, as this was the stage when additional effects were added in the film laboratory: double exposure, masking; while the sound was provided only in the print production stage. The non-camera films have many of the features of unique work and, just like negatives, they are the source for all other copies. However, they are not tantamount to a ‘master copy’ in the digital domain — and, for this very reason, they call for a creative interpretation in the course of optical printing.

Klatka z filmu Juliana Antonisza

Klatka z filmu Juliana Antonisza

Klatka z filmu Juliana Antonisza

Klatka z filmu Juliana Antonisza

Klatka z filmu Juliana Antonisza

In traditional film technology, the original is the ‘master print’ recorded on film — which, however, is prone to decay and ceases to be a reliable source after several years. What is more, no filmmaker was ever able to control the process of producing subsequent copies and their conformity with the aforementioned ‘master print’, which is why audiences are not necessarily presented with what the filmmaker intended to show. This also contributes to the ambiguity of the concept of the ‘original’ in the case of film material and creates the need to use many source materials. Both the template, as well as the print cannot be identified with the original, yet both include its features. Based on the properties of the original non-camera materials held at the Filmoteka, we have decided to consider the non-camera films as the original model as far as the aesthetic aspects are concerned, and at the same time, to treat the negatives as the point of reference with regard to form and content. In light of the above, the negative was the source for the digitisation, while we relied on fragments of the original non-camera films in the colour correction process. Shot after shot, we compared the effects from the digital projector with the hand-painted film frames. This made it possible to restore the original density and lighter tone, and, above all, the vivid colours of ink and felt-tip pens. Achieving these properties, found in the non-camera films, would not have been possible if we were to rely solely on the optical printing methods in the laboratory.

Another specific issue that came to the fore in the course of the project was related to the digital restoration of Antonisz’s works. While transferring the films from the analogue (film) into the digital (file), we wanted to retain as many properties of the non-camera image as possible. One of the defining properties of Antonisz’s original technique is its unique character. Each frame is unique, in that it is characterised by different colour intensity and paint texture, which produces an additional effect of deformed shapes and pulsating images during projection. The advanced digital tools available today make it possible to smooth out aspects of film image which are irritating to the eye. In this case, however, due to the unique way in which the film was made, we have decided that the author has the final word: ‘Pulsation is the definition of life [...] Besides, the slight vibration of the drawing is a specific feature of Non-Camera. [...] It’s my handwriting, my style.’[15] How to retouch an image that was subjected to such intense use already in its making: scratched, punctured, torn, stained, where the amount of scratches far exceeds that known from film work of the past? We should let the artist speak: ‘What is most important is the expression of the work rather than its technical perfection.’[16] For this reason we have decided, along with the team of digital restorers, that, as we are unable to differentiate between intentional ‘damage’ done by the artist and that resulting from improper handling, none of it should be removed. What is more, in this case, the scratches and stains are not a ‘layer of patina’ (as some tend to see the damage in old films), but constitute a full-fledged means of expression that convey the materiality and fragility of the film medium. In consequence, we only chose to remove the white spots which were definitely secondary and resulted from dirt on the negative.

Polska

The film 'A Few Practical Ways to Prolong One’s Life' is a particularly interesting case. This ‘film about film’ includes live-action sequences, noncamera fragments, as well as filmed stock. It would be difficult to find a better and more condensed pretext for a reflection on what should and what should not be restored, how to approach damage, the marks of time, and the characteristic aesthetics of the ‘narrow format’. This is where we have relied on the experience of art conservators from such seemingly distant fields as painting and sculpture. The non-camera insertions, being an example of unique handicraft, could not undergo digital restoration — just as one does not remove the traces of tools, eliminate the damage occurring in the course of the creative process, or ‘mistakes’ that result from the author’s use of a given technology; all this is an integral part of the work.

Another issue we had to consider while restoring Antonisz’s films, was the way he used his own machines, tools, and materials to achieve the effect of consistency in a work. The non-camera films, due to their formal and technological complexity, and the numerous traces of direct and intentional intervention by the artist, connect the distant realms of film archiving and the conservation of traditional works of art. They make us aware that the work of the archives goes beyond the negative and the copy — that, in some cases, film archivists need to abandon the traditional framework and methods, moving towards new, interdisciplinary conservation strategies that combine their current practice with the experience of contemporary art conservators, art historians, and advanced post-production laboratories.

[1] Julian Antonisz, Film skończył się z nadejściem braci Lumière…, int. Jan Fejkiel, "Kultura" (Paris) 1980, no 27, p. 12.

[2] Paweł Sitkiewicz, Polska szkoła animacji, Gdańsk: słowo/obraz terytoria, 2011, p. 195.

[3] Julian Józef Antonisz, Manifest artystyczny eksperymentalnego studia filmów animowanych przy Muzeum Filmu Animowanego non-camera, "Kino", no. 11, 1986, p. 15.

[4] Jan Fejkiel, Namalować film, "Sztuka", no. 4, s. 46.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Bogdan Zagroba, Film bez kamery, czyli oko w oko z Julianem Antoniszem, "Film", no. 32, 1977, p. 14.

[7] Katarzyna Emil, Pantograf, chropograf i Antoniszczak, wywiad, "Film", no. 51, 1983, p. 10.

[8] Fejkiel.

[9] The company founded by the Pathé brothers in 1896 became one of the largest film production companies in the world. As a result of the company’s dynamic development, the market for early hand-coloured films was dominated by the French. Due to its complex infrastructure, (in 1906 its factories employed ca 600 female workers), Pathé had no direct competition at the time. See Jorge Dana, Niki Kolaitis, ‘Colour by Stencil. Germaine Berger and Pathécolor’, Film History, vol. 21, no. 2, 2009, pp. 180–83.

[10] Diagram drawn by the artist; in the archive of artist’s family.

[11] Fejkiel.

[12] Zagroba, p. 15.

[13] Julian Antonisz, quoted in Wojciech Roszewski, Dla oka i ucha. Wynalazek Juliana Antonisza, "Argumenty", no. 28, 1977.

[14] Antonisz, Manifest artystyczny eksperymentalnego..., p. 15.

[15] Julian Antonisz, Film skończył się…

[16] Zagroba