overview

overview

The movie “Salto”, in a manner similar to other Konwicki novels and movies, takes us on an oneiric journey to the recesses of a human soul. A stranger arrives in a somnolent little town. He calls himself Kowalski-Malinowski and claims that he has lived there during the war. He wanders around the town and strikes up strange conversations with the residents, as though he were trying to reconstruct the past. Maybe he is only a buffoon talking rubbish, but who secretly wants to be recognized as a prophet? However the townspeople need someone who could become a legend and who could rise above the everyday humdrum. They will even follow him in a somnambulistic dance, called „salto”. In the morning Kowalski's wife arrives and debunks him publicly. The crowd pelts the would-be prophet with stones.

storyline

storyline

A man in his forties jumps off a rolling train. He is in the middle of nowhere. He walks across country and gets to the nearest small town. His nervousness is in a sharp contrast to the sleepy atmosphere of the town. He knocks at somebody's door and claims that he has lived there. He introduces himself as Kowalski-Malinowski. The host, though surprised, welcomes him in. Kowalski falls asleep in the attic room but has a nightmare: partisans come to execute him. He jumps out of bed and starts chatting with the host. It turns out they both have been suffering from insomnia.

In the morning Kowalski meets a girl who is the spitting image of another girl, Maria, he used to know. It turns out it is her daughter - Helena. They talk. Then Kowalski tries to dig something out of the ground in an orchard. He chases away a boy who watches him from behind a bush. He finds a grenade and when he throws it away it explodes. Suddenly, the boy's father, a poet, appears and threatens him. Kowalski shares his fears with Helena – he’s constantly on the run from someone. Helena wants him to kiss her.

Blumenfeld, who remembers Kowalski from the past, appears. He talks about hiding away during the war. Blumenfeld invites him to an anniversary celebration in the evening. Cecylia does a tarot reading for Kowalski: he is star-crossed soul and he will know no peace. Kowalski does not believe her and starts to pick on her. He draws a humorous horoscope for her but he hits the nail on the head as Cecylia has actually been waiting for her husband to come home after the war. Eventually Cecylia chases him away while he is saying she has insulted a prophet.

Kowalski continues his search in the orchard. Blumenfeld comes and demonstrates his acting talent. A cavalry captain interrupts them and invites them to the river to show them three beauties swimming. The Captain does not believe Kowalski. He pulls him aside and asks him for the real purpose of his visit. When Kowalski starts giving a prophetic speech, the host arrives asking for help with the boys who got poisoned by something. Kowalski takes responsibility for curing the boys in front of the gather residents of the town. It is a chance for him to get even with the poet for his hatred of him, as the boys are his sons. The poet accuses Kowalski of hypocrisy. The residents do not understand the argument between them. Kowalski wants to leave the town but the host stops him.

Kowalski and Helena meet a local drunkard and beau all rolled into one. As opposed to the Hamlet-like main character, it takes him two whistles to make a girl come over to him.

Kowalski falls asleep in the orchard. This time he dreams about Germans who want to shoot him. When he wakes up he sees all the residents digging up the orchard in search of Nazi treasure.

Helena returns home. Kowalski gets another chance to arouse her interest in him. He falls into a lofty converastion but actually he gets bogged down in lies. In fact, it is hard to discern what is true and what is false. Helena smiles indulgently. In a surge of passion Kowalski tries to take her and she consents. After that Kowalski unexpectedly shows her stigmata on his hands.

In the evening the host takes Kowalski to the community center for the anniversary celebrations. A decadent atmosphere prevails in the venue. Various weaknesses of human nature are revealed. The local drunkard and beau all rolled into one is dancing with all the women, though deep down he longs for a real love. Other men are illicitly drinking alcohol. Drunk Kowalski gives his prophetic speech. Everyone dances the waltz. The poet recites poems. The host confides that he cannot do bad things. Blumenfeld wants to leave the town forever. Someone drinks a toast to the host's health and then bites the glass. The cavalry captain wrestles with Kowalski. The new day dawns. In his drunk vision Kowalski, like Christ, takes on the sins of others and like Christ he ends up crucified. When he rouses from the vision, he starts a somnambulistic dance called „salto”.

In the morning Kowalski's wife and children arrive in the town. She publicly debunks him and orders him to go back home. The townspeople bear a grudge against him, not for lying, but for leaving them, and they pelt him with stones. Kowalski jumps on the train rolling out of town. (JU)

comment

comment

press review

press review

“How has the past shaped the mentality of an individual? Last Day of Summer and All Souls’ Day both give unambiguously pessimistic answers to this question. They present war as complex and obsessions as an irresistible force that cripples any drive to action, or the ability to achieving calmness today. Salto is their pastiche. Konwicki has taken and further developed Munk's thought that the past is as much a source of inhibitions and maladjustments as it is mythopoetic factor in its own right. One of the Contemporary Dream Book's character prophesies: “We will become a legend and leave a memory that those alive can use.” Salto shows how this legend might be realized. If Konwicki was not so attached to heroic complex, his movie would easily become a satire of national martyrdom. However, Salto deals with myth-making in a tragicomic convention. Thus, a legend may not only be ridiculous but also overfamiliar: the imaginary hero runs away from his wife in Salto while a real hero from Wajda's Love at Twenty is ridiculed in a “Winnie-the-Pooh and the veteran” game. Both heros, from opposite ends, took part in making a legend that suddenly became an ordinary show. […] Konwicki's novels and movies have the same poetics and the same worldview. And while his novels truly gain something when turned into films, movies in their turn have the opposite effect, and lose a lot of their literary quality in adaptation. This literary quality may repel many viewers. Also, the issues addressed in Salto, linked to the experiences of older generations, may not connect with younger audiences. I hope my predictions will not come true because I think Salto is a very ambitious and carefully thought-out movie that pushes the Polish School and Polish cinematography in a direction that is desperately needed.”

Rafał Marszałek, “Polish Myths”, “Present times”, 1965, no 18

posters and stills

posters and stills

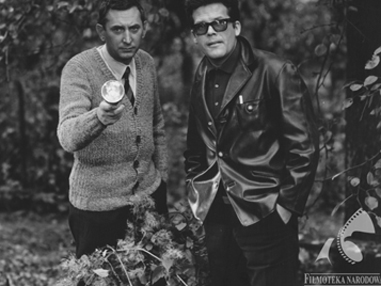

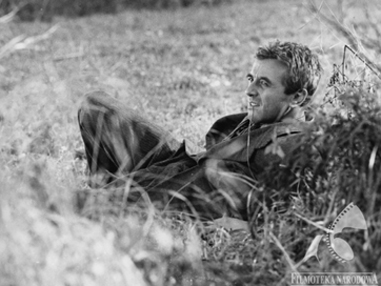

In the photo: Andrzej Łapicki

In the photo: Zbigniew Cybulski

Konwicki's movies do not fall into any category. They are so unique in character that they themselves create a new category. In his third movie all the features of his own original style are present. In fact, there is no great difference between his writings and his movies. It is enough to compare “Salto” with the novel that came before it called A Contemporary Dream Book. In both cases a tragicomic main character, half-prophet and half-fool, desperately tries to find his lost identity in a world full of delusions, apparitions from the past, and symbolic figures. The author's traumas and fascinations from his childhood in the borderlands and from experiencing the war actually only provide a pretext for reviewing the Polish’s traditions of Romantic and martyrological origin. In this film Konwicki’s journey is portrayed in a way similar to many of the films coming out of the Polish Film School during the time, though the filmmaker would argues the greater pathos of his filmic discourse. The main differences manifests itself in the style he uses. Konwicki relies on poetic and surreal visions instead of the cinematic realism favoured by the Polish School; psychological introspection instead of the wider social and historical criticism of the Polish School; and a narrative flow which comes like a chain of associations, full of surprises, unclear situations, and oblique statements instead of the clearer narratives favoured by the Polish School. In the past the movie has been labeled as controversial, as many audiences found the non-linear narrative difficult to follow. Today, this meandering style has its own charm. What really strikes us today instead is the verbosity of “Salto” as a film. (JU)